We interview Nina Scott of Tanda Tula

The big personality spearheading change at Tanda Tula.

In this latest blog, we get to know Nina Scott – the vivacious, big personality with an even bigger heart, who is part of the team spearheading change at Tanda Tula, one of South Africa’s most beloved safari camps.

The beginning of the story

It’s bright and early on a Thursday morning when Shaun and I meet Nina virtually for our interview. I haven’t had any coffee yet and can feel it, but Nina is poised, well dressed and lively, despite our early appointment. We ask her to explain how she ended up at Tanda Tula.

She gathers her thoughts for a moment.

“I’m a very lucky person. I am not a South African, but my mother is South African, so that was the connection to the continent. I grew up all over the world – have lived on three different continents in more than 10 countries. I was born in Thailand, and lived for many years in Southeast Asia – including Indonesia, Singapore and the Philippines. We then lived in Europe – in Portugal, Spain, Holland, France, and the UK.

“I am Dutch by nationality, so I have a strong northern European connection, but I don’t really feel Dutch. I feel very privileged to have been able to choose South Africa. I had traveled many times to South Africa with my mother, and at a very young age fell in love with the bush. That amazing, nostalgic energy that the Greater Kruger has, really dug deep into my veins.”

“I always had a passion for South Africa, so after I finished university in France and in the Netherlands, I decided to return to South Africa in 1994/95.”

She pauses for a second.

“This is the land of milk and honey guys. Not the United States, not Asia. Africa is the continent of milk and honey. There is so much amazing, innovative stuff happening here. So I wanted to be part of that, but I didn’t really have the lodge industry on my mind at that time.

“I worked in a number of different businesses, including the military aerospace industry.”

She laughs openly at the shocked looks on our faces.

“That’s where I met my husband, Don. He’s an aerospace engineer, a bit of a rocket scientist. The company was half South African, half French, and I because I spoke fluent French, I was there to do a lot of the marketing. That was a real experience,” She laughs.

She goes on to explain that although her and Don were doing well financially, the industry they were involved in weighed heavily on them, and overnight they decided to walk away from it and get a better quality of life.

They were travelling in the Timbavati region when Nina called a good friend who owns one of the camps south of Tanda Tula, and asked out of interest if he thought than she and Don could make it in the lodge industry, despite having no knowledge of life in the bush. To her surprise, he offered them a job on the spot! They sold everything they had accumulated in their cosmopolitan lives in Johannesburg. The house, the Porsche, the business suits – everything had to go!

Nina smiles reflecting on the decision that turned her life upside down.

“We had no telephone and no electricity – just a radio and less than 10% of what we were earning in Johannesburg, but I have never been richer in my life.”

Eventually, Don and Nina realized that they wanted ownership of their own camp. So together with their partners, they took over Tanda Tula, just up the road from where they had been working when they made their move from Johannesburg.

Success stories of surviving a global pandemic

Like all tourism businesses, Tanda Tula was hit hard by the Covid 19 pandemic.

Nina explains:

“Our first priority was to hold onto the 65 staff members that work for us. Each one is the primary bread winner in their families, which means that about 10 people are dependent on each staff member. So that was our number one priority – save the staff. Number two – save the business. It was hectic. We hemorrhaged something horrific, but once you’ve learned how to eat beans, you can do it again.

“Our partner who owns the land Tanda Tula operates on decided he wanted to buy into the brand as well. It was a brilliant partnership with him, and a real Hail Mary. We’re very, very fortunate to have him on our team. And we’ve managed to keep every staff member employed. So many of them have been with us for more than 20, 25 years. We have an amazing team.”

Making waves in the safari industry

Shaun now asks Nina about some of the plans Tanda Tula has for expansion in the future, but she has something else on her mind.

“Sorry, but while we’re on this point, there’s something else I want to talk about”, she says.

“When we first bought into Tanda Tula, Don and I had learned there was a serious problem in the safari industry. There is a high turnover of staff, especially in management. We had found that often the staff that were in management had come up though the lines, and they had been excellent guides or spa therapists, but they had no management skills. So we decided that at Tanda Tula, we would select key partners to join us on the journey, but they must be operations partners.

“These are not shareholders who are sitting in Joburg or Cape Town or flipping Switzerland. These must be people that are on the ground, and they must have ownership in this company. If I’m not mistaken, I think we are the only brand in South Africa that has that split in a very realistic way – not a BEE situation, where they’re sitting on a board of directors and don’t know what they’re talking about.

“These are people with very, very skilled operations knowledge that we made part of our team. And I would attribute a lot of our success to that model. It builds a sense that we are in this together. There’s a strong collaboration. We are not changing the rules every five minutes.

“In fact, just after the Covid nightmare, we had the entire team back in camp, and we did a huge presentation to them, where we put up a big screen and we showed all the renderings for the new camp.

“We received a standing ovation. So many of the staff came to us and said ‘you make us feel safe’. I did not see that coming. I saw an opportunity for growth – to spread the love and spread the money, but they saw safety.

“I really realized how important this transformation is for us. Not only for us as a brand, or for the market out there that’s looking for something new and fresh and a happy story, but for my team. That is the most important thing. I didn’t realize how much this would impact them in such a positive way.”

Changing the safari narrative

Nina goes on to answer our questions about the relocation of the Tanda Tula Field Camp, where guests can enjoy the wilderness without complications. She then begins to talk about conservation in South Africa, and changing the narrative of the safari industry.

In a world where there is so much vying for our attention, and where so many people flit from occupation to occupation without ever really delving into one, it is a privilege to listen to Nina talk about what she is truly passionate about. For her, Tanda Tula and the work they are doing is not just a way to earn a living. It is part of something much bigger – something she really believes in and has dedicated her life to.

“Since about 2017, I’ve been on a mission to decolonize safari,” she says.

“In multiple articles and white papers, I’ve read about various decolonizing efforts on the continent. What I’ve learned is that Africans are specialists at decolonizing, but decolonizing with empathy.

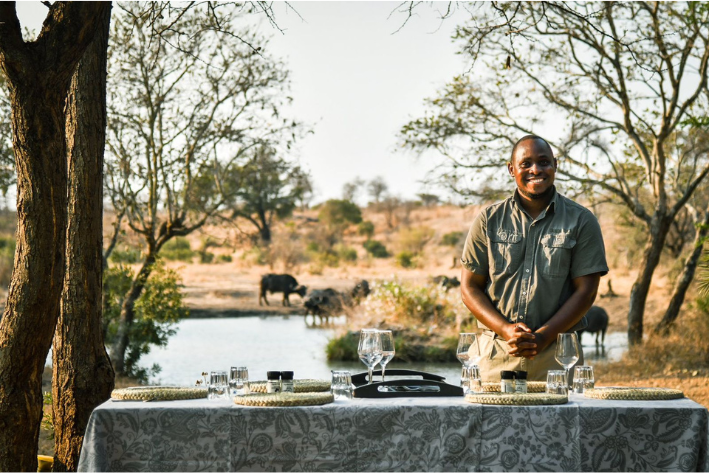

“In the safari industry, we are all guilty of depicting Africa as this vast wilderness destination. There’s this herd of giraffe moving across the scene, but you don’t actually see any of the humans, the Africans, the indigenous people. And when you do see them, you don’t see them in the landscape – they’re servants, bringing you a glass of champagne.

“This is a narrative that we all need to start changing. How do we visually represent Africa in the safari industry? We need to think very carefully about the subliminal messages that we’re sending out there. So it was a big mission of mine to transform the Tanda Tula brand into one of those leading brands that is on an empathetic decolonizing journey. We are creating a brand that is inspired by Africans, owned by Africans, and delivered by Africans. It’s the modern safari revolution.”

Nina goes on to talk about including South African culture in the safari experience at Tanda Tula. She reflects on how in East Africa and Namibia, local culture is an important part of the safari experience, but in South Africa, there is not nearly enough understanding of the humans that inhabit the landscape. They are trying to change that – encouraging their staff members of all ethnicities to share their uniquely South African stories.

Community projects that change lives

As you can imagine, conservation initiatives at Tanda Tula follow the same thoughtful approach as the operational business does. Nina recounted some incredibly eye opening stories.

“All of us in the Greater Kruger region exist in a five-star bubble, and no matter what kind of good work any of us does, it’s very superficial unless you really get down to the bottom of things.

“For example, recently I’ve been working with an NGO called Wild Shots. They are photographers who go into the community and they teach young people about photography. All of these young people are unemployed, and I brought one on board – a chap called Innocent. He was 26 years old. After he saw his first rhino and went on his first game drive, he said to me, ‘Nina, all I could think of before I came here was, why is the South African government spending so much money to protect this one animal? Isn’t it better if they just shoot all the rhinos, get rid of all of them, and then the government will maybe take that money and put it back into our communities where we need water, we need electricity, we need education, and we need healthcare. So maybe we should just shoot all the rhinos now.’

“It was mind blowing. This was coming from a 26 year old in our own community. We have to become relevant in the eyes of our communities, and doing little bits of jobs here and there, like painting schools, is not going to cut it.”

Nina goes on to tell us about some of the other conservation and community projects Tanda Tula is involved in.

One example is an initiative they are working on with a group called ‘Inclusive’, who help small businesses to develop and become viable and robust. In the Timbavati specifically, they are working at creating a supply chain economy, where they can find consistent suppliers within the community. Doing so will allow them to put money back into these small communities right on their doorstep in a sustainable way.

The other project Tanda Tula is focusing on to build relevance with their community is education.

“The government has hugely failed the youth of this country with education,” Nina explains.

“It is absolutely abysmal. Rural South Africa has been entirely forgotten. If you go to Zambia for example, every guide, tracker, chef, host, waiter, and housekeeper speaks really good English. So much better than South African people, who are not educated in English. And this is the problem, because it makes the barrier to entry very low in our industry. You don’t have to have a matric to apply with me.

“You need to know some stuff if you’re a guide, a tracker or a chef, but the bulk of the staff is hired on personality and willingness to learn. But that’s also no good if you can’t string one sentence of English together. You’ll be put into the scullery and housekeeping and bush squad, no matter what your abilities are or what your potential is. And for this reason, we started an adult literacy program 8 years ago.

“We also have a scholarship program. I approached a few of our key staff members a few years ago, who have longevity with us and a real passion for the work they do. I asked them if they’d like profit shares in the company or if they’d like us to send their children to the private school where our kids go to school.

“Every single one of them said ‘educate my child’. Isn’t that incredible? We live in rural South Africa where cash is king, and every one of them chose education over the money. That says a lot.”

Poaching in the Timbavati: A problem close to home

After chatting with Nina about the various community projects Tanda Tula is involved with, Shaun asks Nina about how the antipoaching units in the area work.

“So anti-poaching units are organized by the Timbavati as a whole,” Nina explains.

“Guests pay a conservation fee for every night they are in the park, and all of that money goes towards the management of the greater region we are a part of, and towards this epic antipoaching team we have. Poaching in the Timbavati is a real, dangerous wildlife crime, and our team puts their lives on the line on a daily basis.

“The stakes are really high here, and so the team is paid properly. This is not a minimum way situation, which as you know, is South Africa’s national sport,” she says wryly.

“We all support these guys and their families with extra funds, and so from that perspective, we have a good thing going. But if we don’t build an appreciation for our wildlife economy in our communities, what is going to happen when poaching ends?

“Do we think that these crime cartels are going pack their bags and move back to China, Vietnam, Nigeria, or wherever they came from? No, they’re not. They’re going to stick around and make life hell for us. They will switch from poaching to something else. So more than ever, we need to build this robust economy – not painting a school or buying a colouring-in book.

“That’s why we are on this mission. We have to be more relevant. If we don’t get this right now, we can kiss all this goodbye. A few years back I interviewed another youngster and I asked him if he’d ever been to the Kruger. And he said, no, but his aunt works there, so he had some kind of connection with the park.

“I asked him what happens in the Kruger, and he told me what there’s ‘meat’ or food there, and that the white people go to look at the food. When I asked if it was better to have the Kruger or a platinum mine, he chose the platinum mine.

“This is our problem. We perceive these wild destinations as a privilege and a luxury, but not everyone sees it like this. And that is Don’s and my biggest mission. If we’re going to do anything, we’re going to change this.”

Nina’s passion oozes into every word she speaks. The early morning is forgotten and we’re running overtime but no one seems to care. She’s speaking with such fervor that all I can think is that it is a privilege to be sitting here listening to her. When last did I talk to someone who feels so strongly about their work? When will be the next time I encounter someone else with the same passion?

Although there are some other individuals and camps doing some incredible work, Nina tells us that there aren’t a lot of people on the same mission.

“I think it costs us nothing to empower one person – to bring on someone like Innocent who said lets shoot all the rhinos. We can provide apprenticeships to so many people out there like him, but people are afraid of too much work, of too much admin.

“That is where the buck stops with these guys. They just cover their eyes and they say, no, we paint the school and we tell our guests to ‘pack for a purpose’. People put their blinkers on.

“But we are prepared to put in the work. It requires time, it requires patience, it requires research, and we’re not getting paid for it, but we understand the value, because I want this area to be around for my grandchildren one day.

“I want every grandchild of all my staff members to realize that there is this massive opportunity on their doorstep that they want to be part of, and they don’t have to run off to Joburg or anywhere else to have a good life. It’s hard work, and people don’t like hard work. But that’s why we’re going make it easy for them. We’re going do it and we’re going to make it easy for them.”